Last week I looked at whether Ontario’s experience with the double cohort in 2003 could offer some lessons for the coming years. If large numbers of students decide to take a gap year this September and enrol in September 2021, the planning processes adopted in 2003 might bring some order to an enrolment surge.

Sadly, Ontario higher education’s recovery from current circumstances may take longer than anyone would wish. Some lessons about how things can go wrong can be found in our system’s grimmest postwar decade, the 1970s.

The 1960s, of course, are remembered as years of glory: new campuses, new buildings, new programs, ample opportunities to become tenure-track faculty, and additional government funding for every new student. University enrolments grew by 70% between 1967 and 1971. Colleges, still in their infancy, doubled their enrolments in the same period.

The late 1960s were also years of excess. The new universities had ambitious growth plans and strived to become as comprehensive as their older peers. J. A. Corry, who later became the great principal of Queen’s University, recalled that the “scramble to get into graduate studies … resembled a gold rush.” Student groups criticized what they saw as indifferent teaching and impersonal institutions. The government appointed a commission in 1969 to recommend how the postsecondary system could become more focused.

1971 was the year the music stopped. The number of students applying to university that fall flatlined at some universities and declined at others, confounding all experts. An unusually high number of upper-year students did not return. No one knew if this was a one-time event or a long-term change.

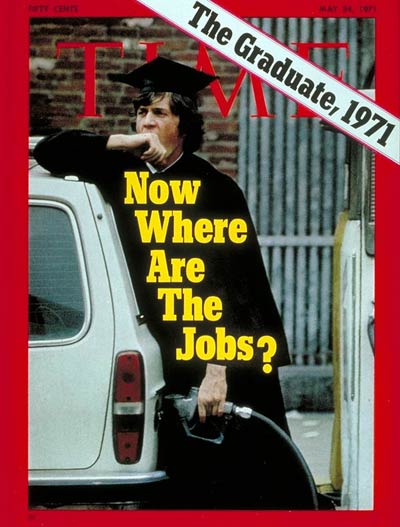

As it turned out, university undergraduate enrolments were stagnant from 1971 to 1973, then grew from 1974 to 1976, and then were flat for the rest of the decade. College enrolments showed a similar pattern. The idea that higher education was a ticket to a good career stopped catching on. Gas station attendants were the baristas of their generation.

The reason was that the economy stopped growing in 1970, and it grew in fits and starts through the decade. There were severe recessions in 1973-74 and 1979-80. Employers could not absorb all the baby boomers, even those with a higher education.

Students fell out of love with higher education, and so the government did, too. Premier William Davis told a journalist in 1972 that the high cost of higher education, student activism and a shortage of jobs for some graduates had reduced public support for higher education. The policy consequences were severe:

- Facing an unexpected revenue slowdown and the obligation to pay for the new OHIP program, the government cut funding to universities and colleges in real terms. (This feat was somewhat disguised by annual inflation rates that averaged 8% over the decade.)

- Fearing the wrath of discouraged young voters, the government froze tuition fees for four years.

- The net effect was that total university operating revenue (from government grants, tuition and fees, per student, measured in constant dollars) fell by 23% between 1970 and 1982. At colleges, the decline was more than 30%.

- The government placed a moratorium on new capital construction in 1972, which remained in place until the mid-1980s.

- The government stopped approving university proposals for new graduate and professional programs.

- By the end of the decade, both the Ontario Council on University Affairs (one of HEQCO’s forebears) and the Council of Ontario Universities were calling on the government to either provide more money or reduce the scope of the universities’ mandate. A committee headed by the deputy minister recommended that, if more money was unavailable, some universities should be closed.

It was not the Dark Ages, but it was as close to them as anyone would want to see.

No one knows what will happen to enrolments in current circumstances: they might be affected for a year, or a decade, or maybe not at all. That was true in 1971, too. We might draw a few lessons from the 1970s experience.

The first is: Don’t let young people fall out of love with higher education. Higher education institutions and the government should continue to join forces to make sure that the students who attend higher education – in whatever numbers – receive the best experience they possibly can. This includes providing fair value for the money students pay, being mindful of the students who are least able to help themselves, and working with employers to maintain work-integrated learning.

The second is: Don’t let current circumstances fracture relationships between institutions and the government. These have taken a long time to build. The next few years are bound to have financial disappointments that could easily lead to an endless exchange of blame and recrimination. No one won this war in the 1970s.

After the 1970s, it took a while for students to fall back in love with higher education. It took much longer for the government to wholeheartedly embrace higher education as a driver of Ontario’s economic and social well-being. If we stumble into repeating the mistakes of the 1970s, the consequences could last for a very long time.

David Trick is interim president and CEO of the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario.