A recent study outlines an approach that can help universities predict where, and when, to intervene with student supports. Taking a cue from K-12 research — where experts have long studied predictive factors related to overall achievement — the authors show how GPA and credits achieved in a student’s first year of study, and whether the student enters university directly or indirectly from high school, have an important relationship to graduation.

Authors: Rob Brown and Gillian Parekh

School-based transitions and academic pathways shape the lives of students dramatically. We know this from three decades’-worth of public education research in Ontario.

Students’ key points of transition include entry into elementary and secondary settings, as well as transitions into postsecondary settings or the workforce. Each transition point is important. But the opportunities afforded to students throughout their educational journeys also have a cumulative effect, which often results in stratified outcomes.

K-12 research outlines many predictive factors related to students’ overall academic achievement. For instance, studies show that the combination of special education placement, suspension and absenteeism can have detrimental effects on students’ likelihood of accessing PSE. Conversely, secondary students’ participation in academic pathways, specialized programs and special education are closely related to high school graduation and postsecondary access. Grade 9 credit accumulation has been predictive of high school graduation for over a generation. Understanding these key relationships helps districts assess schooling conditions created through historical policies and practices — and then provides opportunities to intervene.

Researchers at a Southern Ontario university and a local school board set out to answer this key question: what if universities could develop a tool, similar to one used by K-12 researchers, that would help predict when and where interventions can best support students to graduate?

The collaborative research project focused on over 11,000 students who a) started Grade 9 in a large urban district school board between 2003 and 2007, and b) transitioned into university. The majority (61%) made a direct transition to university from high school. Another 39% made an indirect transition (i.e., arriving from another postsecondary institution, or having taken time off from school before attending).

Our research focused on three factors: students’ first sessional GPA, credit accumulation at the end of students’ first year and how students arrived at university (either direct or indirectly from high school). We found that all three factors matter. First-year university GPA had a strong relationship with graduation; most students with a GPA of 4 (a grade of C) or higher graduated. Those with a GPA of 3 (or a mark of D) or lower were less likely to graduate. Likewise, students who completed 15 credits (note that a full course load is 30 credits from September to April) or more were likely to graduate. Direct-entry students were much more likely to graduate from university than indirect-entry students.

Our earlier examination of students’ direct and indirect entry revealed important patterns around access and other forms of privilege (Parekh, Brown & James, 2020). In our study, students entering university directly were:

- more likely to have identified as female,

- more likely to have been born in Canada,

- more likely to have access to two parents,

- more likely to have taken academic-level courses in Grade 9 and

- less likely to have a history of special education as compared to their indirect pathway peers.

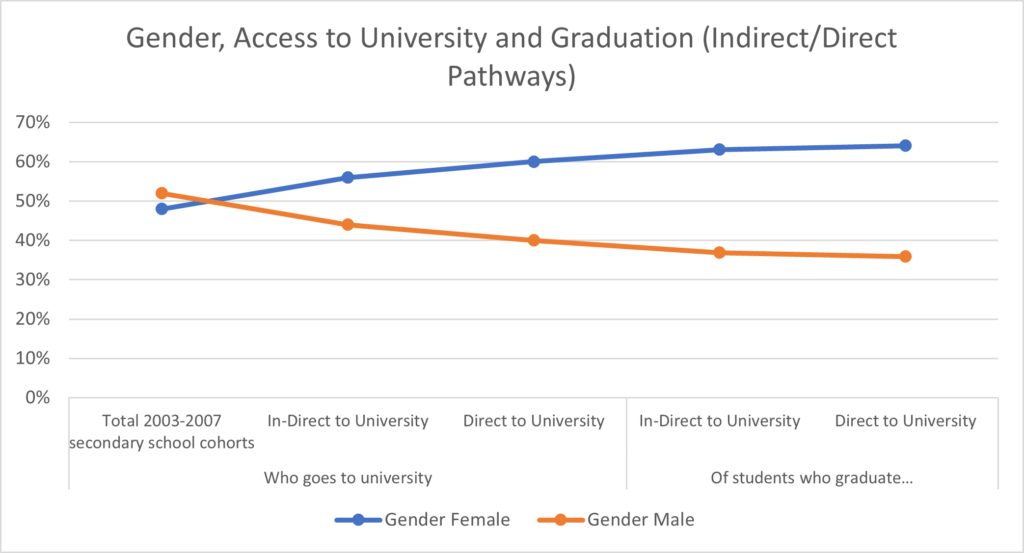

For example, Figure 1 below shows the relationship between gender, pathway, access and graduation from university. There is a 20% access gap for direct-entry female and male students; but this gap jumps to 27% between male students who arrive indirectly to university compared to direct-entry female students. This suggests that students’ identities, as well as how students transition from K-12 education, can shape (or influence) postsecondary pathways and outcomes.

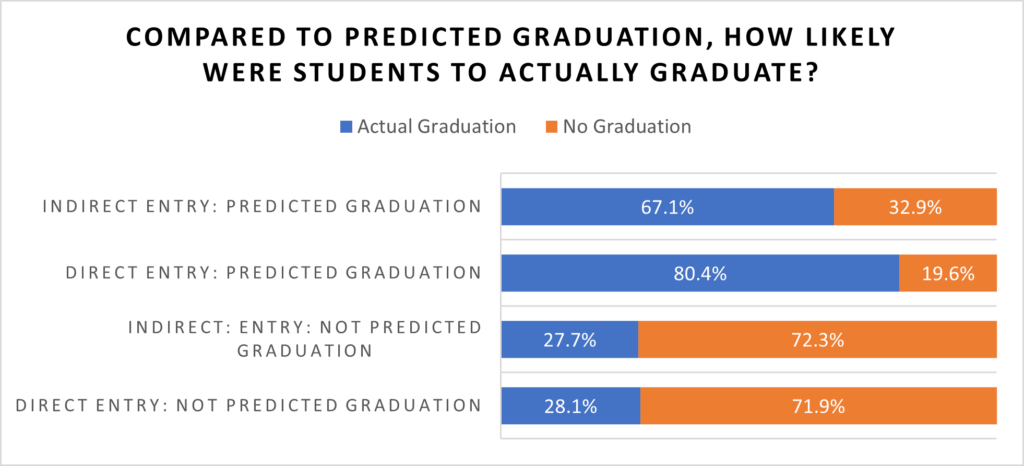

To develop the graduation predictor measure, we combined students’ first-year GPA and number of credits completed. We also examined whether students arrived directly or indirectly from high school.

For direct entrants, having a GPA of C or higher and 15-plus credits is strongly related to graduating with a degree (80%). For those arriving indirectly, having a GPA of C or higher and 15-plus credits is a less accurate (while still strong) predictor of graduation (67% compared to 80% graduation).[1] Students with fewer than 15 credits or a lower GPA (3 or lower) in their first year are unlikely to graduate, regardless of whether they arrived directly or indirectly (both approximately at 28% actual graduation). Moreover, indirect-entry students were much less likely to have a higher GPA or have accumulated a higher number of credits than their direct-entry peers.

Though these factors may appear to be measures of individual achievement or commitment to education alone, they may also indicate the conditions and opportunities afforded students along their educational pathways.

Arriving at university for the very first time is a key life transition, and not all students have had the same access to preparatory experiences. But there are strategies universities can adopt to support students. For instance, if students’ first-year GPA and credit accumulation are critical determinants for student graduation, universities might consider additional interventions that directly support students’ first years of study.

Additionally, if a student’s entry pathway is another key predictor of university graduation, universities may also want to consider the multiple roles and responsibilities students carry — both inside and outside the school. Relevant questions for university staff include the following:

- How could universities offer further opportunities for students to develop their study skills and learning strategies, particularly in their first year of study?

- Are the courses offered through the university adopting inclusive pedagogy and enabling curricular entry points for all students?

- How can programs integrate flexibility and accommodations to support students who may have multiple roles and responsibilities outside the school (e.g., caregiving roles, employment etc.)?

This research offers universities practical approach that can be used to examine their own student populations and the conditions in which students are asked to learn. As a result, institutions can be more responsive in supporting students as they transition into and through postsecondary education.

Notes

[1] Part of this lower graduation rate for low-risk indirect students may be because some indirect students were graduate students, who were entering university after undergraduate studies elsewhere. For these students, they may not have had enough time to finish longer graduate programs.